A cybersecurity incident response plan (CSIRP) is a documented strategy that clarifies how an organization will respond to malicious actors and cyber threats.

The overarching objectives of a CSIRP are to:

Minimize the impact of security breaches.

Restore normal operations as quickly as possible.

Limit harm to the organization’s data, reputation, and finances.

Why are CSIRPs important?

Cyberattacks are increasing in prevalence and severity, with the average small business losing $39,000 to malicious actors.

What’s more, a 2024 MYOB survey found that 60% of mid-sized Australian businesses had experienced a cyberattack or related incident.

These attacks are also becoming more sophisticated. Keeper Security’s survey of more than 800 IT leaders reported that:

51% had experienced AI-powered attacks.

36% had experienced attacks from deepfake technology.

35% had experienced cloud jacking.

34% had experienced IoT and 5G network-related exploits.

The above data shows that cybersecurity incident response plans have never been more crucial. The most obvious benefit is that they provide structured protocols to swiftly respond to threats.

On a broader level, CSIRPs ensure business continuity, protect sensitive data, and increase organizational resilience.

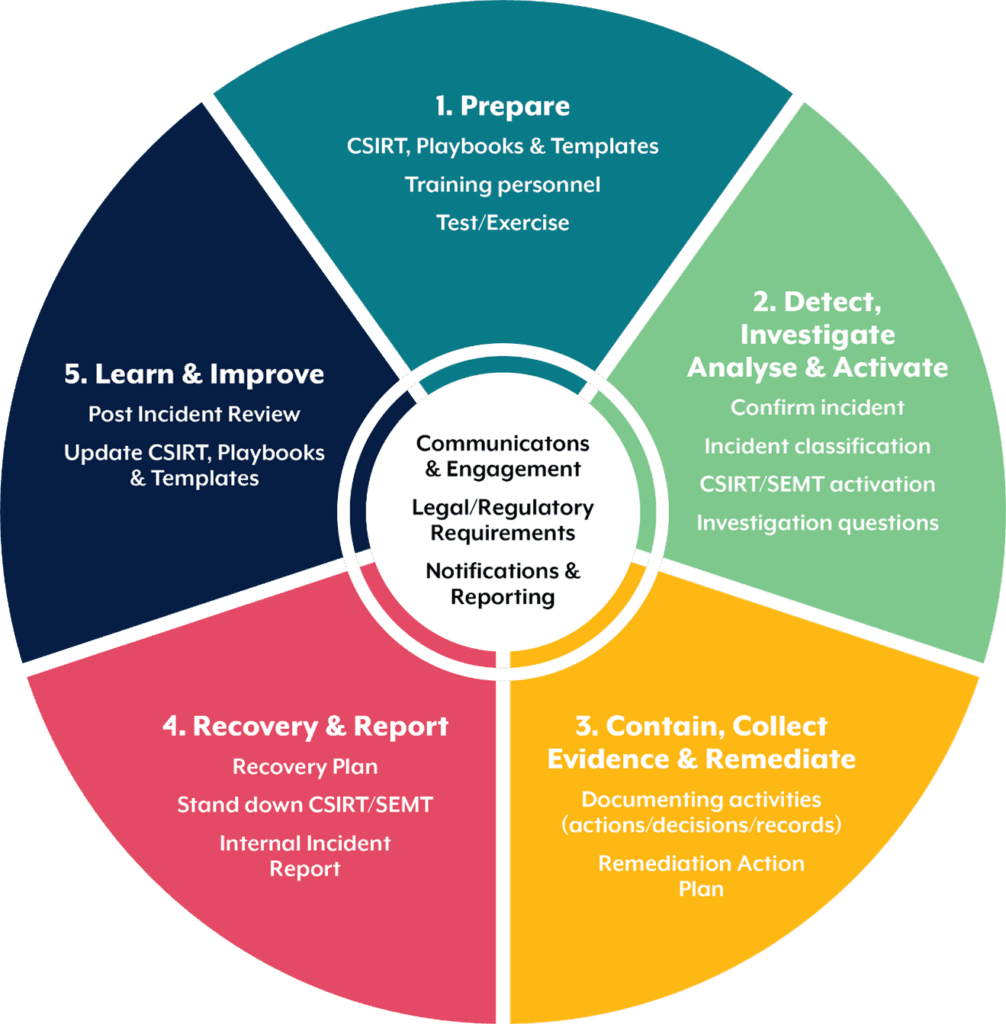

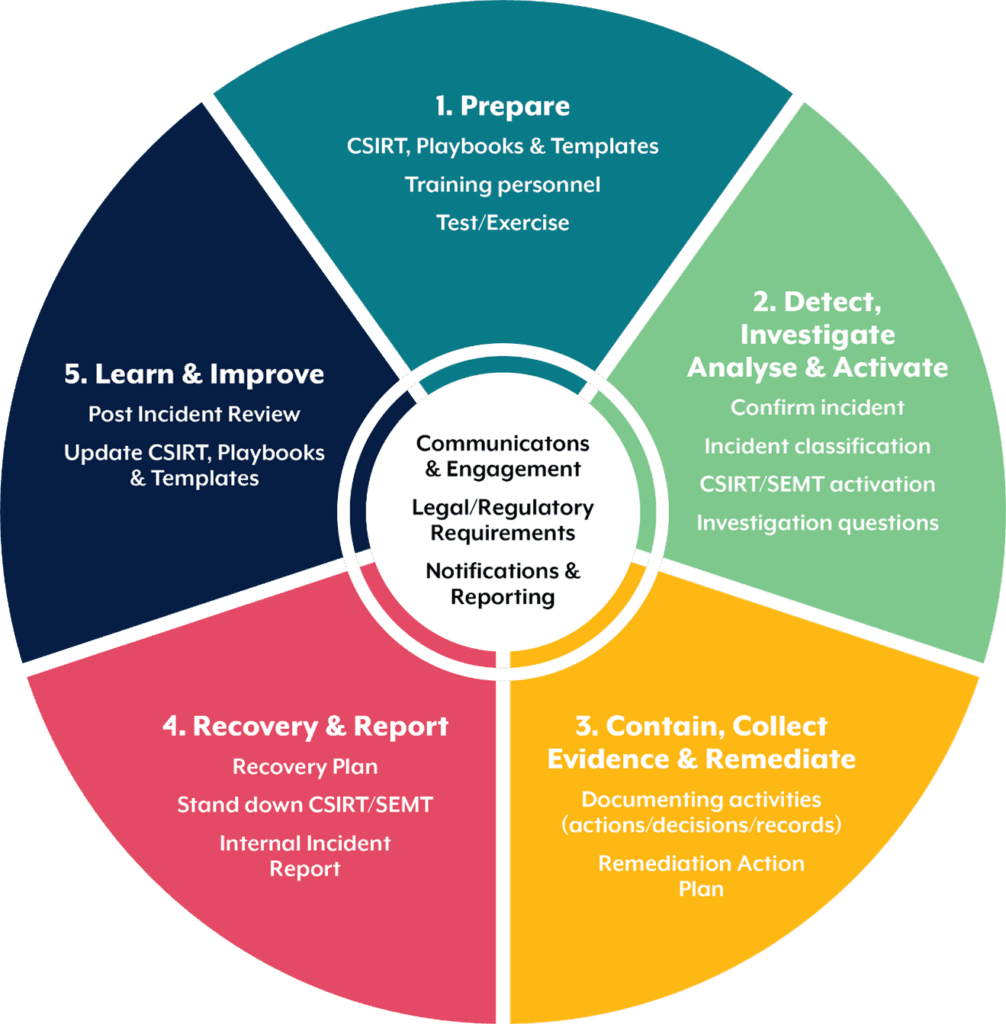

Key phases of a cybersecurity incident response plan

The particulars of a CSIRP will vary from one business to the next, but the most effective plans take inspiration from five phases defined by the Australian Cyber Security Centre (ACSC).

1 – Prepare

The most prepared organizations are those that have a CSIRP in place before a security breach occurs.

Preparation is a broad and multi-faceted topic. Nevertheless, robust incident response plans should detail:

Members of the incident response team: what is their role in the response and what are their contact details? Have they been trained to deal with incidents?

Issue tracking and storage: how and where will issues be tracked? Where will evidence and other sensitive information be stored?

Incident reporting and communication: what mechanisms are in place to report incidents? Do employees have an encrypted way to communicate with each other?

Policies and procedures: do these provide clear advice on how to respond to security breaches?

Response position: will the organization pay ransoms? Will it report incidents to the government, acknowledge cybersecurity incidents in public, or share information with trusted partners?

2 – Detect, Investigate, Analyse & Activate

The second phase comes into play when an incident has occurred and the organization needs to respond.

Threats take many forms and are constantly evolving, so it is impossible to devise a plan for all of them.

However, a good starting point for any CSIRP is to consider the most common methods of attack:

Unauthorized data extraction.

Suspicious changes to files, file names, and locations.

Desktop messages demanding payment to unlock a system.

Unexplained slowness in a PC, workstation, or network.

Ransom notes in file directories.

Normally reliable systems that suddenly become glitchy.

Atypical file encryption.

Repeated failed attempts to access company resources.

Investigation

If a potential threat has been identified, the CSIRP must account for how it would be investigated. Investigation involves comparing unusual activity or behavior to baseline data and if necessary, preserving that data as forensic evidence.

The investigation sub-component also determines how a business would respond if alerted to an anomaly by a third-party security provider or the ACSC.

Analysis

Analysis involves a systematic examination of the threat to understand its nature, scope, and impact.

Analysis should also clarify how incidents are categorized, classified, and prioritized as well as how data is stored and transmitted.

In sensitive cases, out-of-band transmission (such as communication that occurs over Slack) may be necessary.

Activation

In this context, activation is the mobilizing of a cyber incident response team (CIRT) to manage the threat or incident.

As we touched on earlier, roles and responsibilities should be pre-assigned.

3 – Contain, Collect Evidence & Remediate

Most incidents require containment before they overwhelm a company’s resources or inflict further damage.

Containment is a critical part of the incident response process since it gives teams time to develop a tailored remediation plan.

Central to the remediation plan is decision-making. Should the system be shut down or disconnected from the network? Do certain functions need to be disabled?

In any case, the best course of action depends on:

Damage to (or theft of) resources.

Availability of services – such as network services or services provided to customers.

The need for preservation of evidence.

The resources needed to enact the plan.

Duration of the solution – some plans may call for an emergency stopgap of a few hours or weeks while systems are restored, but other solutions will be permanent.

Collect evidence

Evidence collection is important should the matter progress to legal proceedings. But the business must collect evidence lawfully lest it be inadmissible.

Examples of evidence include IP addresses, databases, screenshots, CCTV, network packet captures, social media posts, and configuration files.

Evidence should be stored in a secure location and be ready to present to third-party stakeholders.

Data should also be kept in an evidence log that details:

Remediation

With the threat contained and evidence collected, a remediation action plan must be devised.

This plan outlines what actions and resources are required to resolve the incident, who is responsible, what systems should be prioritized, and how long remediation is expected to take.

4 – Recovery & Report

In the fourth phase, the organization must craft a recovery plan to explain how compromised networks, systems, and applications will be restored to normal operations.

Recovery also calls upon the organization to detail:

How systems will be monitored to ensure they are running at full capacity.

How vulnerabilities will be strengthened to avoid similar incidents in the future.

An internal incident report for future reference.

When key personnel such as the Cyber Security Response Team (CIRT) and Senior Executive Management Team (SEMT) will be stood down.

5 – Learn & Improve

In the fifth and final phase, a Post Incident Review (PIR) should be conducted.

The review should include a root cause analysis and a debrief on the incident response itself.

To that end, the seven-part PPOSTTE Model is sometimes used to reflect on what went well, what could be improved, and whether the incident could have been prevented.

NIST incident response framework

The NIST incident response framework (formally the NIST Cyber Security Framework 2.0) was developed by the National Institute of Standards and Technology in the United States.

NIST – who developed the framework as part of its duties under the Federal Information Security Management Act – details standards and best practices around information security for federal agencies.

NIST has also released a number of security incident handling guides tailored to non-government organizations.

Some are listed below.

Quick-Start Guide for Creating and Using Organizational Profiles

This publication helps develop organizational profiles to understand, tailor, assess, and prioritize cybersecurity outcomes.

Profiles are based on factors such as the threat landscape, the business’s mission statement, and stakeholder expectations.

A Guide to Creating Community Profiles

This NIST framework assists organizations with developing community profiles for cybersecurity risk management.

Note that the term “community” denotes a group of organizations with shared interests, objectives, and contexts. They may be grouped by sector (e.g., critical infrastructure), technology (e.g., the cloud), or other use cases.

Small Business Quick-Start Guide

This release targets small and medium-sized businesses with modest or non-existent cybersecurity plans. Included under this umbrella are non-profits, small government agencies, and schools.

The small business publication is not a standalone product but instead supplements the NIST Cyber Security Framework (CSF) mentioned earlier.

Summary:

A cybersecurity incident response plan (CSIRP) is a comprehensive strategy designed to guide an organization through a threat posed by a malicious actor.

With cyberattacks increasing in prevalence and sophistication, CSIRPs not only prepare organizations for threats but also make them more resilient as the nature of threats evolves.

CSIRPs are broad and sometimes complex documents, but most take inspiration from a five-phase framework developed by the Australian Cyber Security Centre (ACSC). The five phases help organizations prepare for attacks and then detect, contain, remediate, and recover from them.

In the United States, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is an authority on cybersecurity risk and protection. Once targeting Federal agencies exclusively, NIST has now published a range of guides for non-governmental organizations.

References